Jo Haynes and Magda Mogilnicka

University of Bristol, UK.

Images of city-dwellers flocking to urban parks in large, spontaneous gatherings to enjoy the sunshine, fresh air and space as we emerge from the coronavirus lockdown, prompted us to wonder, if parks were imagined to be the lungs of cities in the early 19th century, what are they today?

When the coronavirus effectively shut down the festival for the summer, as a research team examining music festivals across Europe, we had to decide whether to change our focus and methods or pause the research until festivals returned next year. We began to wonder whether our sample of festivals would survive the hiatus and if the pandemic would irrevocably change the idea of the festival forever. In a recent blog, Simon Frith (2020) suggests that ‘what is currently assumed to be the way festivals have to be is, in the long view, merely a moment in the history of festivals, a moment that could now be coming to an end’. If that is the case, what will they look like next time around? As a team of critically reflexive researchers, we decided it was better to continue following the changing context and meaning of the festival, come what may.

However, another event happened far from the south-west of England which further altered how we thought about Bristol’s festivals – the police killing of George Floyd and the renewed anger and visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement. In our city, those events and the BLM protests it prompted locally, resulted in the ‘Colston topple’ – the statue of the 18th Century slave-trader Edward Colston was pulled from its plinth and rolled to a watery grave in the docks near-by. The statue that had come to symbolise the city’s struggle with its participation in the enslavement of thousands of African people – was gone. For many years, Colston’s legacy and the statue commemorating this, has been at the centre of a city and nation-wide debate focused on the ignored and problematic dimensions of the history of this and other port-cities that economically prospered from involvement in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade (Dresser 2009).

Following the Colston topple, we began to imagine the pasts of other spaces around this city – not the statues, not the gothic or Georgian buildings – the ordinary spaces and places, the parks nearby, the roads, paths and lanes we walk through. What histories are enfolded in those spaces? How do those histories and memories shape how we occupy and move through and around the city?

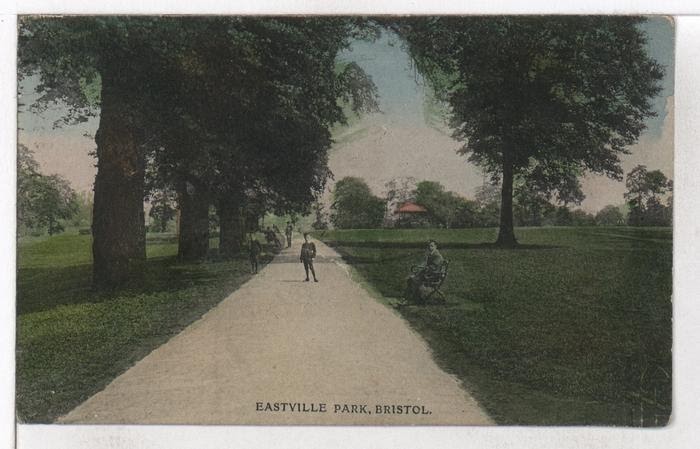

Eastville Park (Fig. 1), is where an annual 2-day music festival – Love Saves the Day – normally takes place in late May, championing house, drum & bass and dub and attended by approximately 50 thousand people over the weekend. The festival alters the grassy spaces into a mélange of colours, sounds and smells, with multiple stages, designs, immersive experiences, and festival goers enjoying carefully curated beats and tunes. It transforms the normally, tranquil space of relaxation for families and friends into an alternative reality, full of dynamic energy, where, as one of the organisers explained, people are pushed out of their comfort zones.

The park itself occupies land adjacent to a busy motorway (M32) and the north of the park borders the River Frome. It has a lake with ducks and swans, a boat house, and in the park’s south-east corner there is a car park, tennis courts, bowling greens, a playground and pavilion. The pathways that traverse the grassy site are flanked by a variety of mature trees and surrounding the lake itself there are specimens of Hornbeam and Scots Pine (the latter is apparently the largest in Bristol). There is also a derelict swimming pool.

The land for this park was purchased from Sir Greville Smyth by the Bristol City Council for £30,878 in 1889 and in 1894 an additional portion of land was bought for £1,227. Greville Smyth was one of the descendants of John Smyth, a Bristol merchant whose wealth originally derived from the transatlantic slave-trade. Over the course of four hundred years, the Smyth family descendants channelled a portion of their wealth into the purchase of land and the restoration of properties (e.g. Ashton Court mansion). In a city whose wealth and prosperity, along with the development of the built environment, came from the slave-trade (Dresser 2000), it is no surprise to find that Eastville Park is also entangled in this cruel and inhumane history.

Public parks were created in many of Britain’s large cities in the 19th Century to provide some respite from the squalor and dense living conditions that many people had to endure. Indeed, in Bristol a pamphlet was produced called, ‘A Cry from the Poor: a letter from Sixteen Working Men to the sixteen aldermen of the city’, asking for a ‘people’s park’ to be created in working class areas of the city. The parks in other more salubrious areas such as Clifton Downs and Brandon Hill were not convenient for those living in the working class areas of the city such as Eastville/Fishponds and Bedminster, two important industrial areas for tobacco, and the coal and tin mining industries.

Throughout this time, parks were thought to provide clean air and promote healthy activity in cities – hence, the image of them as the city’s lungs – especially those parks situated at the edges of a city’s industrial areas. In addition to assumptions about their health giving properties, the impact of public parks in urban areas was also framed through the idea of social control, and according to Carole O’Reilly, ‘parks were supposed to offer alternative “rational” recreation to absorb the leisure time of the new working class of the industrial towns’. Parks were envisaged as spaces to ‘implement middle-class moral imperialism’ (2019: 10-11). With their health benefits and regulatory mechanisms for their use– don’t litter, pick flowers, or climb trees – the success of public parks as ‘civilising spaces’ for the Victorian era was contingent upon park users acting in a compliant manner.

This summer our parks, woods and fields are without music festivals, but they are now teeming with life as those living in dense areas of large cities in particular, confined for 10 (or more) weeks by a virus that attacks the respiratory system, head to parks to breathe again. But the sanitised aspect of urban parks is less apparent. The media images circulating of some recent large gatherings, alongside accounts of human waste left in boxes as the park’s facilities remain shut, brings to mind the rubbish strewn canvas of an empty festival field following days of excess and bacchanalia, with little clusters of tidied garbage here and there as gestures of compliance.

Festivals transform urban parks (and other sites) into places of escapism from everyday life, providing an opportunity for people to let their guard down and express themselves beyond the constraints of social norms – exuberance, intoxication, extravagant fancy dress, glitter and stylised make up are acceptable social practices at festivals – breathing life and possibility into weary workers that move across the city or, that is the promise. But just as festivals are imagined as spaces of freedom, they are also sites of social control, carefully managed by festival organisers and city authorities. The ‘unconventional’ behaviour acceptable during festivals is bounded by gates and fences, guarded by security, hemmed in by roads and city ordinances. The apparently uncontrolled behaviour is regulated within the spatial and temporal confines of the park, where the music stops at a certain time and the rowdy, unkempt festival goers must leave.

Despite recent actions that forced us to imagine the past differently through the ritualistic toppling of an unjust city statue, our cities remain in a recovery position from the pandemic, and they are not ready to consume the burst of energy brought by festivals. Our parks are now required to take a break, to breathe calmly and rebuild their strength. And their convalescence has enabled us to reflect on the history of the urban park, while remembering there will be festivals of some kind in the future.

Jo Haynes and Magda Mogilnicka

University of Bristol, UK.

References

Dresser, M. (2000) ‘Squares of distinction, webs of interest: Gentility, urban development and the slave trade in Bristol c.1673–1820’ Slavery and Abolition 21 (3): 21-47.

Dresser, M. (2009) ‘Remembering Slavery and Abolition in Bristol’ Slavery and Abolition 30, (2): 223 –246.

Frith, S. (2020) Home thoughts on festive occasion Live Music Exchange (blog 18/06) https://livemusicexchange.org/blog/home-thoughts-on-festive-occasions-simon-frith/O’Reilly, C. (2019) The Greening of the City: Urban Parks and Public Leisure, 1840-1939 New York: Routledge.